Towards the ultimate limits of artificial neural networks

When light is scattered, how precisely can a measurement result be inferred from this light? We explored the limits of what is possible using artificial intelligence.

No image is infinitely sharp: no matter how precisely you build a microscope or a camera, there are always fundamental precision limits that cannot be exceeded in principle. For example, the position of a particle can never be measured with infinite precision; a certain amount of uncertainty is unavoidable. This limit does not result from technical weaknesses, but from the physical properties of light and from the transmission of information itself.

We therefore posed the question: What is the absolute precision limit that is possible with optical measurement methods? And how can this limit be approached as closely as possible? We succeeded in calculating the ultimate limit for the theoretically achievable precision, and also managed to develop artificial neural networks that come close to this limit after appropriate training. This strategy is now to be used in imaging processes, for example in biomedical imaging applications.

An ultimate limit to measurement precision

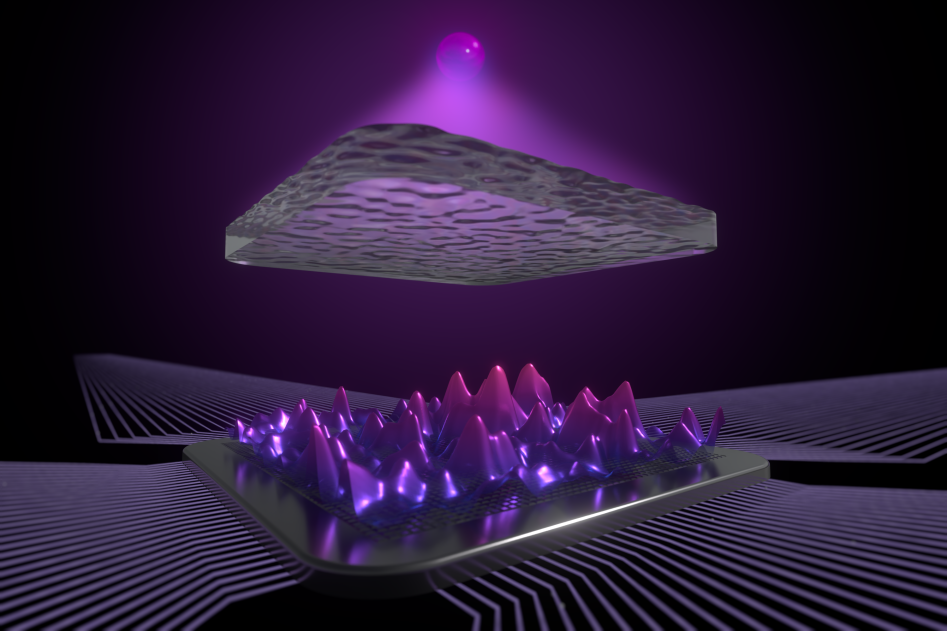

To illustrate how challenging optical imaging can be, we can imagine that we are looking at a small object located behind a shower curtain. Because of random light scattering by the curtain, we do not just see an image of the object, but a complicated light pattern consisting of many lighter and darker patches of light. The question now is: how precisely can we estimate where the object actually is based on this image, and what is the ultimate limit to the achievable precision?

Such scenarios are especially important in biophysics and medical imaging. Indeed, when light is scattered by biological tissues, it appears to lose information about deeper tissue structures. But how much of this information can be recovered in principle? This question is not only of a technical nature, but physics itself sets a fundamental limit here.

The answer to this is provided by a theoretical measure: the so-called Fisher information. It describes how much information a noisy optical signal contains about an unknown parameter, such as the object position. If the Fisher information is low, a precise determination of the parameter value is not possible, no matter how sophisticatedly the signal is analyzed. Based on the Fisher information, we were able to calculate an upper limit for the theoretically achievable precision in optical experiments.

Neural networks can learn from chaotic light patterns

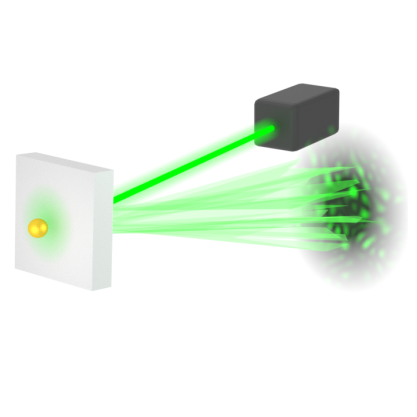

In a proof-of-principle experiment that we conducted, a laser beam was directed at a small, reflective object. This object was located behind a turbid liquid, so that the recorded images only showed highly distorted light patterns. The measurement conditions varied depending on the turbidity: the larger the turbidity, the greater the difficulty of obtaining precise position information from the measured signal.

To the human eye, these images looked like random patterns. But by feeding many such images (each with a known object position) into a neural network, the network could learn which patterns were associated with which positions. After sufficient training, the network was able to determine the object position very precisely, even with new, unknown patterns.

A precision close to the physical limit

Particularly noteworthy: the precision of the network predictions was only slightly worse than the theoretically achievable precision calculated using Fisher information. This means that the artificial neural networks implemented in this study were not only effective, but also almost optimal, as they came close to the ultimate precision that is permitted by the laws of physics.

This realization has far-reaching consequences: with the help of intelligent algorithms, optical measurement methods could be significantly improved in a wide range of areas - from medical diagnostics to materials research and quantum technology. In future projects, we want to work with partners from applied physics and medicine to investigate how these AI-supported methods can be used in specific systems.

This study has been published in Nature Photonics (Starshynov et al., 2025).